Semiconductors are humanity’s crown jewels, a physical manifestation of the skills that have skyrocketed our species to the top of the food chain. Despite our skirmishes and flirtations with genocide, humans have an innate urge to cooperate and when we do there’s no stopping us. These chips, the things inside our TVs, smartphones and ICBMs, they’re just as much art as tech; the brushstrokes of our brightest minds cascading across our screens.

Chip War by Chris Miller is like deep-fried broccoli, delicious on the outside and nutritious on the inside. The book is divided into several dozen short chapters and I thought this structure worked well. The attention to technical detail is interesting without being cumbersome, and the cast of characters is limited enough that we don’t get lost in a phone book. In short, I enjoyed this book and I reckon you might too.

Last year, the chip industry produced more transistors than the combined quantity of all goods produced by all other companies, in all other industries, in all human history. Nothing else comes close.

Precision manufacturing was essential, since lithography was now so exact that a thunderstorm rolling through could change air pressure—and thus the angle at which light refracted—enough to distort the images carved on chips.

Like so much of the tech that dominates our lives, the semiconductor industry started in California. While it’s tempting to grieve for a business that started here and has ended up over there, after reading Chip War I no longer feel so bad about the loss.

In a hypothetical world in which all things semiconductor remained in America, we wouldn’t have made nearly as much progress as has been possible with multinational manufacturing. Producing semiconductors is so staggeringly expensive that international cooperation, capital and subsidies is the only way to sustain Moore’s law.

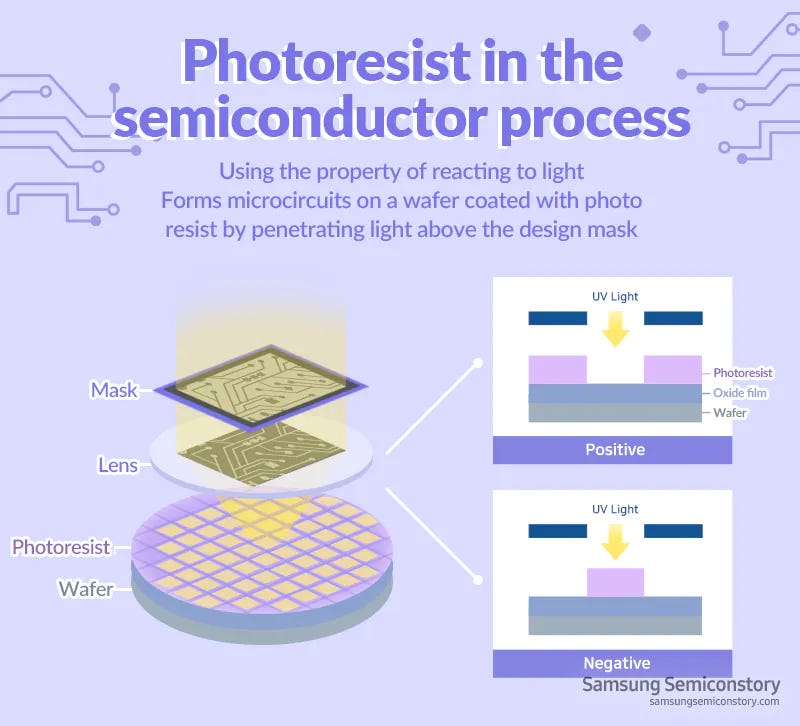

Semiconductors are produced with a technique called lithography. A photoresist chemical is sprayed onto a silicon wafer. Ultraviolet (UV) light is then shone through a mask which carves a pattern into the chemicals. Here’s an explanation of the process from Samsung’s website.

Photoresist is a type of photosensitive material which undergoes a chemical change in reaction to light. — When a photosensitive material is exposed to light, the parts exposed undergo change, and the parts not exposed to light remain unchanged. This allows for certain patterns to be created. The process of developing photos makes use of photosensitivity.

Photoresist hardens or melts when exposed to light. This makes it possible to expose photoresist to light selectively, creating prominences and depressions like those in a printing block.

Older and less sophisticated semiconductors were relatively simple to produce, involving little more than an off the shelf UV lightbulb. However, as the designs for new chips have continued to shrink a different light source was needed. UV light has a minimum wavelength of ~193nm, which limits how far manufacturers can shrink a chip.

To get around UV’s limitations, researchers had to spend several decades devising a reliable method of producing extreme ultraviolet (EUV) light. EUV has a minimum wavelength of ~13.5nm, which is small enough to manufacture today’s modern chips.

You can’t simply buy an EUV lightbulb. — The company’s engineers realized the best approach was to shoot a tiny ball of tin measuring thirty-millionths of a meter wide moving through a vacuum at a speed of around two hundred miles per hour. The tin is then struck twice with a laser, the first pulse to warm it up, the second to blast it into a plasma with a temperature around half a million degrees, many times hotter than the surface of the sun. This process of blasting tin is then repeated fifty thousand times per second.

The laser, one of mankind’s most sophisticated inventions, contains exactly 457,329 component parts. It’s housed inside ASML’s lithography machine, which costs $180 million and requires years of training to use. This is one complex beast! For instance, “the installation process of ASML's High-NA Twinscan EXE 150,000-kilogram system required 250 crates, 250 engineers, and six months to complete.”

Producing advanced semiconductors, however, has relied on some of the most complex machinery ever made. ASML’s EUV lithography tool is the most expensive mass-produced machine tool in history.

This level of technical complexity is ludicrously expensive and delicate, which puts the semiconductor industry in a tricky position. The supply chains must work and the right people must be at their jobs. There is no room for error and, unlike in other industries, no alternative sources of supply.

If Saudi Arabia disappeared the price of oil would triple, but we could lean on Russia and Norway in a pinch. We could drill more wells, throw money at fracking, go wild with the tar sands of Alberta, etc. Alternatives exist. If ASML’s factories were blown up, however, our tech sector would be lost. The semiconductor industry exists on a precipice, held aloft by delicate ropes of cooperation that could easily be severed if we’re not careful.

The geopolitics of semiconductors

Beijing, however, is more worried about a blockade measured in bytes rather than barrels. China is devoting its best minds and billions of dollars to developing its own semiconductor technology in a bid to free itself from America’s chip choke. If Beijing succeeds, it will remake the global economy and reset the balance of military power.

China is scared.

China is scared because like any modern nation, their country would cease to exist without semiconductors. China now spends more money on microchips than oil, and a significant portion of that supply comes from America’s allies.

Cutting-edge chips are produced in just two countries: South Korea and Taiwan. And ASML, based in the Netherlands, is the only company in the world that produces lithography machines capable of churning out current generation chips. In the event of war, China’s access to semiconductors and semiconductor manufacturing equipment would be (severely) curtailed.

It’s far easier to control choke points in the chipmaking process when so many essential steps require tools, materials, or software produced by just a handful of firms. Many of these choke points remained in American hands. Those that didn’t were mostly controlled by close U.S. allies.

They say that it takes an entire community to raise a kid. For the tech industry it takes a coordinated world to create a semiconductor. American chip designers depend on Taiwanese fabricators depend on Dutch equipment manufacturers depend on German laser engineers, and so on. It’s turtles all the way down, and the United States and its allies have a hand in most of it.

The opposite of a beginning

“He who controls the spice, controls the universe.” That’s from Dune. Substitute semiconductors for spice and you’ve got an apt description of how important these little silicon trinkets are to the world’s prosperity. Semiconductors are the foundation of modernity, and access to cutting edge chips is this century’s equivalent of last century’s who’s got the most nukes.

In the last few months I’ve particularly enjoyed non-fiction books like The Tiger, Enemy of Mankind and Tracking the Wild Coomba. While these books are interesting, they’re not especially practical. Siberian tigers are dangerous, but unless my life takes a turn for the strange I’ll never need to use that knowledge. Chip War is different, the book is laden with that which will make you sound smart at a cocktail party, and help you to make sense of the daily news. To close out this review I’ll share two interesting facts about semiconductors and the industries they effect.

First, why is NVIDIA going gangbusters? It’s all about their GPUs. These processors were originally designed for graphics rendering, but have proven to be excellent at training AI models as well. NVIDIA is soaring because Wall Street is treating the company as a proxy for investing in artificial intelligence.

GPUs, by contrast, are designed to run multiple iterations of the same calculation at once. This type of “parallel processing,” it soon became clear, had uses beyond controlling pixels of images in computer games. It could also train AI systems efficiently. Where a CPU would feed an algorithm many pieces of data, one after the other, a GPU could process multiple pieces of data simultaneously.

Second, the chip shortage in the auto sector was largely self-inflicted by corporate incompetence.

Politicians around the world have therefore misdiagnosed the semiconductor supply chain dilemma. The problem isn’t that the chip industry’s far-flung production processes dealt poorly with COVID and the resulting lockdowns. There are few industries that sailed through the pandemic with so little disruption. Such problems that emerged, notably the shortage of auto chips, are mostly the fault of carmakers’ frantic and ill-advised cancelation of chip orders in the early days of the pandemic coupled with their just-in-time manufacturing practices that provide little margin of error.

Those damn automakers!

Further suggest reading

El Gato Malo wrote an excellent article about why the semiconductor industry is mostly immune to going woke. When this much precision is on the line, there is no time for an illogical, emotion-driven creed.

There are another eight quotes I saved from the book but which didn’t fit into this review. You can read them here.

My (paywalled) review of Peter Zeihan’s book, The Accidental Superpower. China is kind of screwed in a lot of ways, not just semiconductor supply chains.

If you enjoy reading this Substack and would like to support my work, an annual subscription is just $40 which works out to an affordable $3.33 per month. Every paid subscription elevates the vibrational energy of the universe, since the extra dollars allow me that much more time to make these articles as epic as possible.

I never knew so much about semiconductors. Interesting how integral they are.

I have four comments to make about the China-US rivalry.

1.) The US does not have Allies. It has vassal states that must suck up to Washington. Any country that shows independence from the US is punished either economically, by political coup or militarily, or all three.

2.) China will catch up in the chip war. It is just a matter of time and resources. Until then, it can get all the most advanced chips it needs for its military on the black market.

Think that they will not catch up? Dream on. In 1945, the US was the only country that had the bomb. Four years later the USSR had it. Now even dirt-poor North Korea has it.

3.) An all out war between China and the US will quickly go nuclear. The US is not willing to fight a new Korean War, especially one on a much larger scale, so within weeks, the US will use one or more of its new tiny nukes to intimidate the Chinese. Within days, the nukes on both sides will fly.

4. American society is starting to become unglued. It is the wokes against the conservatives, the drug addicts and the mentally ill sleeping on the streets against the taxpayers. The education system graduates too many high school kids who can't read or do simple math.