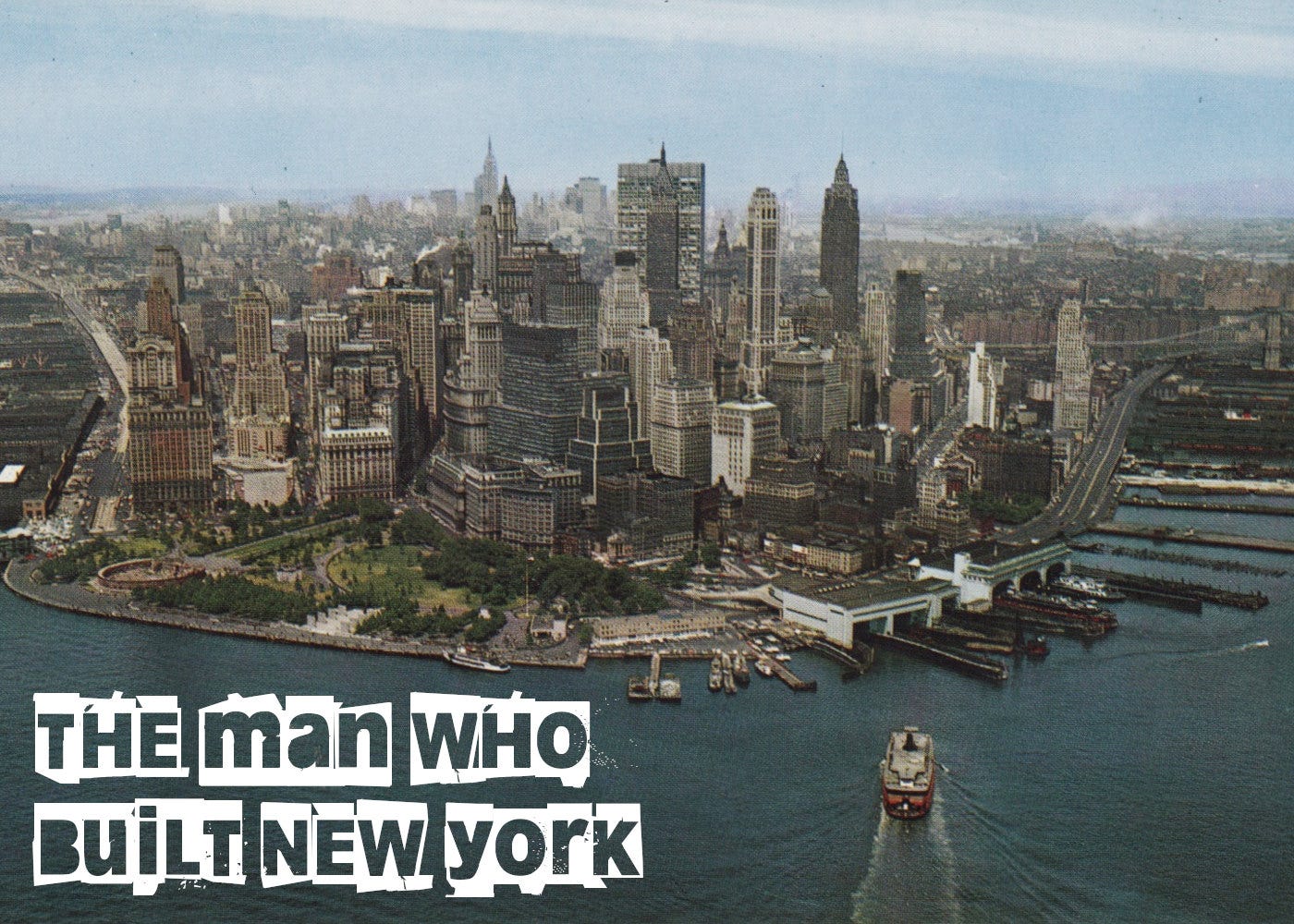

The man who built New York

Timeless themes & character arcs from Ayn Rand's brilliant book: The Fountainhead

Be thee warned! I’m going to spoil major plot points from Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead. Turn away now to keep your sense of wonder alive. Otherwise, let us commence…

In Atlas Shrugged all of country’s most productive citizens are eloping to Galt’s Gulch: a secret commune somewhere in the American Midwest. This large expanse of arable land, nestled among mountains, is shielded by an image projection that’s invisible from the ground but from the air resembles rocky crags and snow-capped peaks.

Only the most creative, intellectually interesting and productive persons are invited to the Gulch, a self-governing coterie of brilliant people producing innovative art, metals, literature, engines and gluten-free bagels that don’t taste like old beer. While superficially appealing, I find that the Gulch raises more questions than it answers.

When the invitations are being issued, where does one draw the line between a productive first hander and an unworthy second hander?

What if a man is a savant chemist with multiple scientific breakthroughs, but every night he smacks his kids before lurching across town to read trashy novels to his mistress? Is productive work the sole arbiter of one’s worth, or is character also a factor?

What if a woman is invited to the gulch because of her beautiful paintings, but after several years she throws her brushes onto the front lawn, stops taking out the garbage and listens to the radio all day while drinking Galt’s Gulchy Grog? Is there a process for kicking people out? Must an excommunicated member be murdered to prevent them from revealing the commune’s location?

Atlas Shrugged is a fantastic novel, but I don’t find it to contain practical solutions to our daily challenges. The real life equivalent of Atlas Shrugged would be getting a second passport for the Cayman Islands and moving there right before America descends into civil war. Appealing, sure, but hardly a viable solution for everyone.

The Fountainhead is more practical in its dispersal of wisdom1. The subtle methods of influence employed by Ellsworth Toohey are being used all the time in our modern world. Peter Keating’s conformity fueled downfall is a dire warning to anyone who would choose society’s suggestions over their own desires. Howard Roark’s heroic arc, from student to famous architect, is a timeless journey of struggle, disappointment and perseverance. So much so that Roark is the most influential fictional character in my life.

That all being said… This review will not be void of skepticism. Not everything in the Fountainhead is worthy of praise, and some plot points and character arcs range from annoying to downright silly. Like any great book The Fountainhead aims for the loftiest realms, but when you fly too close to the sun you’re bound to get burnt. Scars and all, this is what you should know about a man who dreamed of being an architect.

Perseverance: the most prominent theme

Roark announces that he’s dropping out of architecture school and the dean is stunned. Dropping out is not a thing that one does. Furthermore, Roark’s ultra-modern designs are an affront to the dean’s historically informed sensibilities. In this excerpt the dean asks Howard if his blueprints are indicative of his creative intent.

“Do you mean to tell me that you’re thinking seriously of building that way, when and if you are an architect?”

“Yes.”

“My dear fellow, who will let you?”

“That’s not the point. The point is, who will stop me?”

The only future Howard can imagine for himself is being dead in the gutter, or a successful architect. There is no plan B.

That level of conviction is rare in the world, and I continue to find it inspiring. Once you figure out what you’re supposed to do with your life, you’ve got to hold on like you’re dangling from a rope over the polar bear exhibit at the zoo. Let your arms be ripped from their sockets and the skin peel from your palms before you let go.

“But you see," said Roark quietly, "I have, let’s say, sixty years to live. Most of that time will be spent working. I’ve chosen the work I want to do. If I find no joy in it, then I’m only condemning myself to sixty years of torture. And I can find the joy only if I do my work in the best way possible to me. But the best is a matter of standards—and I set my own standards. I inherit nothing. I stand at the end of no tradition. I may, perhaps, stand at the beginning of one.”

Character arcs

For your reading pleasure, please enjoy a summary of the five most important character arcs from The Fountainhead.

Peter Keating

Of the prominent characters Peter Keating’s story is the simplest: he is a feather in the wind. At a young age he expresses an interest in painting, but his mother convinces him to study architecture instead. After graduating he plans to marry Catherine Halsey, the love of his life. However, Catherine is of plain stock and doesn’t know her way around a salad fork. Keating is persuaded to dump Catherine and pursue a woman more appropriate to his rapidly ascending station in life. At every important juncture in his life Peter is convinced to give up that which would make him happy, to chase that which society deems laudable.

Despite being a renowned architect Keating does not even design his own home. Throughout his long career he contributes nothing original to the field of architecture, nor does he prove himself to be an adept draftsman. In a rare moment of honesty this is how Peter describes himself.

“Howard, I’m a parasite. I’ve been a parasite all my life . . . I have fed on you and all the men like you who lived before we were born. . . . if they hadn’t existed I wouldn’t have known how to put stone to stone. . . . I have taken that which was not mine and given nothing in return.”

Peter Keating’s fall from grace is protracted and horrifying. As his architecture firm shrinks from two floors to one, Peter begins to drink without joy. He rekindles an interest in his boyhood passion of painting, but when he shows the canvases to Roark - in one of the book’s most heartbreaking sequences - Roark gently, painfully tells Keating that “it’s too late.” A potent scene, made all the more remarkable by Howard’s reaction after Peter has left.

When Keating had gone, Roark leaned against the door, closing his eyes. He was sick with pity.

He had never felt this before—not when Henry Cameron collapsed in the office at his feet, not when he saw Steven Mallory sobbing on a bed before him. Those moments had been clean. But this was pity—this complete awareness of a man without worth or hope, this sense of finality, of the not to be redeemed. There was shame in this feeling—his own shame that he should have to pronounce such judgment upon a man, that he should know an emotion which contained no shred of respect.

This is pity, he thought, and then he lifted his head in wonder. He thought that there must be something terribly wrong with a world in which this monstrous feeling is called a virtue.

Peter Keating’s life is a painful example of how miserable you may become if you let society dictate your decisions.

Ellsworth Toohey

The antagonist! Ellsworth Toohey, the second most powerful character in the book after Gail Wynand. However, Toohey’s power often goes unappreciated. His tactics for manipulating the wealthy elite of New York are subtle and easily overlooked, but potent nonetheless.

By 2024 I trust that you’re frustratingly familiar with the phrase gaslighting. For those who need a brief reminder: gaslighting occurs when someone (or some organization) tells you that a thing you’ve observed isn’t actually happening. Even when you’re aware that you’re being gaslit the event can still be psychologically jarring.

Ellsworth Toohey employs (to great effect) gaslighting’s underappreciated cousin: lamplighting. To be gaslit is to be told that something you saw doesn’t actually exist. To be lamplit is to be told that something objectively bad is actually good.

Toohey uses his position as a popular newspaper columnist to promote a group of untalented, uninsightful and unscrupulous screenwriters, authors and architects. A quote from Ellsworth.

“What achievement is there for a critic in praising a good play? None whatever. The critic is then nothing but a kind of glorified messenger boy between author and public. I’m sick of it. I have a right to wish to impress my own personality upon people. Otherwise, I shall become frustrated—and I do not believe in frustration. But if a critic is able to put over a perfectly worthless play—ah, you do perceive the difference!”

Here is Ellsworth’s strategy in bullet points.

Promote untalented hacks and their bilge artistry.

Play on the elites’ desire to separate themselves from the working class. Convince the elites that only “refined” people with “delicate sensibilities” can appreciate the so-called masterpieces produced by Toohey’s swinish artists.

As you convince the elites to praise things that are objectively shit, you destroy their artistic discernment, moral compass, and capacity for critical thought. Ellsworth is a master at getting people to believe that the naked emperor is actually well-clad.

“Keating leaned back with a sense of warmth and well-being. He liked this book. It had made the routine of his Sunday morning breakfast a profound spiritual experience; he was certain that it was profound, because he didn’t understand it.”Once one loses the ability to separate beautiful from atrocious, that person will forever return to Ellsworth Toohey to “learn” what is good. Like a moth flying to a lamplight at night, the broken person will mindlessly pursue whatever shiny thing is presented to them.

Ellsworth’s tactics are fucking brilliant. They’re simple, effective, and used everywhere all the time.

This is art.

This is a role model.

This is a woman.

This is a respected intellectual.

These aren’t the droids you’re looking for.

Each time you lamplight a person you reduce their capacity for self-directed judgement. Unsure of objectivity reality, the lamplit increasingly turn to “trusted” third parties, like the mainstream media or government, to tell them what they should think.

What makes Ellsworth fascinating is that unlike the simpletons who execute our modern propaganda, Ellsworth is acutely aware of the game he’s playing. He wants to tear people down to their elemental particles. To shreds you say! Once they’re intellectually broken he rebuilds them as unthinking automatons parroting whatever manure Ellsworth shovels into their sweaty foreheads.

“Make man feel small. Make him feel guilty. Kill his aspiration and his integrity. […] Preach selflessness. Tell man that he must live for others. Tell men that altruism is the ideal. […] Man realizes that he is incapable of what he’s accepted as the noblest virtue—and it gives him a sense of guilt, of sin, of his own basic unworthiness. […] His soul gives up his self-respect. You’ve got him. He’ll obey. […] Kill man’s sense of values. Kill his capacity to recognize greatness or to achieve it. Great men can’t be ruled. We don’t want any great men.”

Dominique Francon

Dominque is said to be the most desirable woman in New York. Despite her sex appeal she remains a virgin into her twenties, a fact we learn from her father. Dominque’s problem with men is that every male she meets is a groveling soy boy, so desperate to bed her that she can’t help but be repulsed.

Roark is the first man she’s actually attracted to, as far as we know, when she sees him breaking granite in a quarry.

And she thought, with a vicious thrill, of what these people would do if they read her mind in this moment; if they knew that she was thinking of a man in a quarry, thinking of his body with a sharp intimacy as one does not think of another’s body but only of one’s own.

In one of the funnier scenes in the book, Dominque tries to smash her marble fireplace so that she can get Roark to fix it. After nearly breaking her wrist with a heavy hammer, she only manages to leave a superficial cut in the stone. This will have to do, she tells herself. The next morning she rides to the quarry and asks for Roark’s help to replace the marred piece. When Roark arrives the following evening he immediately renders assistance.

"There it is," she said, one finger pointing to the marble slab.

He said nothing. He knelt, took a thin metal wedge from his bag, held its point against the scratch on the slab, took a hammer and struck one blow. The marble split in a long, deep cut.

He glanced up at her. It was the look she dreaded, a look of laughter that could not be answered, because the laughter could not be seen, only felt. He said:

"Now it’s broken and has to be replaced."

Events progress and a week later Dominque loses her virginity to Howard Roark, forcefully… One could even use another word to describe the encounter, a word that starts with R. However, we are dealing with shades of complexity as Dominque admits that she had wanted to be taken in this way. One suspects that Ayn Rand being a female is the sole thing that’s saved The Fountainhead from cancellation on account of this graphic scene.

Anyhow… So much more than a beautiful bimbo, Dominque has a sharp mind that despises hypocrisy, corruption and the fallibility of man.

She saw the faces streaming past her, the faces made alike by fear—fear as a common denominator, fear of themselves, fear of all and of one another, fear making them ready to pounce upon whatever was held sacred by any single one they met...

Something of a nihilist, Dominque does not believe that beauty can triumph over squalor. She abhors the world and amuses herself by toying with others. At a gathering of wealthy landlords, Dominque ruins the atmosphere by musing on how their tenements have fallen into disrepair.

"The house you own on East Twelfth Street, Mrs. Palmer," she said, her hand circling lazily from under the cuff of an emerald bracelet too broad and heavy for her thin wrist, "has a sewer that gets clogged every other day and runs over, all through the courtyard. It looks blue and purple in the sun, like a rainbow."

"The block you control for the Claridge estate, Mr. Brooks, has the most attractive stalactites growing on all the ceilings," she said, her golden head leaning to her corsage of white gardenias with drops of water sparkling on the lusterless petals.

Dominique’s hostility is exemplified by her strange behavior towards Roark. After learning that it was Roark who ravished her (prior to this he was just a man from the quarry) Dominque begins scaring off his clients. She starts by convincing Joel, who is on the verge of working with Roark, that he ought to find another architect.

"Good heavens, Dominique, what are you talking about?"

"About your building. About the kind of building that Roark will design for you. It will be a great building, Joel."

"You mean, good?"

"I don’t mean good. I mean great."

"It’s not the same thing."

"No, Joel, no, it’s not the same thing."

"I don’t like this ’great’ stuff."

"No. You don’t. I didn’t think you would. Then what do you want with Roark? You want a building that won’t shock anybody. A building that will be folksy and comfortable and safe, like the old parlor back home that smells of clam chowder. A building that everybody will like, everybody and anybody. It’s very uncomfortable to be a hero, Joel, and you don’t have the figure for it."

Dominique is not chasing revenge, her anti-Roark crusade has nothing to do with their passionate meeting. When Dominque finds beauty in the world her impulse is to destroy it. She admits this freely, the first time that she’s alone with Roark in New York.

"You know that I hate you, Roark. I hate you for what you are, for wanting you, for having to want you. I’m going to fight you--and I’m going to destroy you--and I tell you this as calmly as I told you that I’m a begging animal. I’m going to pray that you can’t be destroyed--I tell you this, too--even though I believe in nothing and have nothing to pray to. But I will fight to block every step you take. I will fight to tear every chance you want away from you. I will hurt you through the only thing that can hurt you--through your work. I will fight to starve you, to strangle you on the things you won’t be able to reach. I have done it to you today--and that is why I shall sleep with you tonight."

This is where The Fountainhead crosses into the fantastical. Dominque’s determination to drive off Roark’s clients makes about as much sense as a fish climbing Mount Everest. You don’t belong there, you dumb fish!

In my experience the tensest moments between a man and a woman happen before they’ve had sex. Early in a courtship I could understand Dominque toying with Roark. She could be intensely curious about him and how he will react to her interference. But after they’ve slept together one might expect a certain bond to form, and for the tension to ease. Well, not in Rand’s world. Instead, what we get is this...

Dominique loves Howard Roark so she uses her beauty and influence to convince clients not to hire him. Then she marries his rival, Peter Keating, because she finds him loathsome. Not long after that sham marriage she divorces Peter to marry Gail Wynand, another man whom she doesn’t love. This marriage continues till the end of The Fountainhead. Only in the final chapter does Dominque give up her self-flagellation and find the courage to be with Roark, the only man she’s ever loved. Here is one of Dominque’s last lines in The Fountainhead.

“Howard... willingly, completely, and always, without reservations, without fear of anything they can do to you or me, in any way you wish, as your wife or your mistress, secretly or openly, here, or in a furnished room I’ll take in some town near a jail where I’ll see you through a wire net—it won’t matter. Howard, if you win the trial—even that won’t matter too much. You’ve won long ago. I’ll remain what I am, and I’ll remain with you—now and ever—in any way you want.

Right, so what the fuck is going on here? Either,

As a man I don’t understand the feminine psychology that led Ayn Rand to write Dominique in this way.

There is a philosophical principle that I’ve failed to grasp.

Rand was puffing on wayyyyyyyy too much wacky tobacky when she wrote Dominique.

Take your pick.

While there are a few pieces missing, I think I can still put most of the puzzle together. Dominque’s character arc is learning how to view the world “as a background.” She must learn detachment, how to be emotionally uninvested in the day’s events. For most of the novel Dominique is portrayed as person who cannot accept that evil triumphs over good, that deformity beats beauty. She has a vendetta on the unjust world and this causes her to do strange things, like marry men she hates.

While Dominque’s story is the most unrealistic in the book, it’s valuable to consider her growth. Dominque learns that the world is out of her control, and she does not need to torture herself over outcomes she cannot influence.

There is a lesson here. I find our current societal trends to be deeply concerning in many ways; there’s an infinite hobgoblin stupidity to sink one into despair. But stop, take a step back and let go of that which you cannot control. Swim in the ocean, build a table, find a way to be satisfied with life. Although she takes one of the most indirect routes in the history of literature, Dominque completes her arc and ends the book happy because she learns that she doesn’t have to allow the day’s events to drive her to depression.

Gail Wynand

Gail is defined by his lust for control. An event early in his life helps to explain his intense motivation to hold sway over humanity.

He was fifteen when he was found, one morning, in the gutter, a mass of bleeding pulp, both legs broken, beaten by some drunken longshoreman. He was unconscious when found. But he had been conscious that night, after the beating. He had been left alone in a dark alley. He had seen a light around the corner. Nobody knew how he could have managed to drag himself around that corner; but he had; they saw the long smear of blood on the pavement afterward. He had crawled, able to move nothing but his arms. He had knocked against the bottom of a door. It was a saloon, still open. The saloonkeeper came out. It was the only time in his life that Gail Wynand asked for help. The saloonkeeper looked at him with a flat, heavy glance, a glance that showed full consciousness of agony, of injustice—and a stolid, bovine indifference. The saloonkeeper went inside and slammed the door. He had no desire to get mixed up with gang fights.

After nearly dying, we are led to conclude that Gail vowed never again to be at the mercy of his fellow man. He gains power so that he can be the one to administer the beatings, rather than take them.

Years later, Gail Wynand, publisher of the New York Banner, still knew the names of the longshoreman and the saloonkeeper, and where to find them. He never did anything to the longshoreman. But he caused the saloonkeeper's business to be ruined, his home and savings to be lost, and drove him to suicide.

When we’re introduced to Gail Wynand he is already the most powerful publisher in New York. The New York Banner is his flagship newspaper, but publicly or privately he also owns another dozen rags, organs and safe havens for yellow journalism. Gail uses his newspapers to shape public opinion, make & ruin political careers, destroy businesses, propel unknown artists into fame, spread slander, and break the largest stories before his competitors.

In a candid moment, Gail describes himself as holding a leash that connects him to all of New York. Gail pulls the leash and the crowd moves where he wants them to go. However, as Gail’s character arc plays out he begins to understand that the man holding the leash is also beholden to the mass at the other end. This is captured perfectly in one of the best paragraphs from the book.

At the supper tables, in the drawing rooms, in their beds and in their cellars, in their studies and in their bathrooms. Speeding in the subways under your feet. Crawling up in elevators through vertical cracks around you. Jolting past you in every bus. Your masters, Gail Wynand. There is a net - longer than the cables that coil through the walls of this city, larger than the mesh of pipes that carry water, gas and refuse - there is another hidden net around you; it is strapped to you, and the wires lead to every hand in the city. They jerked the wires and you moved. You were a ruler of men. You held a leash. A leash is only a rope with a noose at both ends.

Gail Wynand learns - we learn - that the man who collects power is not free. He must behave a certain way to maintain that power, and the actions he must take may go against his core beliefs.

When Howard is denounced by a disgruntled client, Gail steps in to defend his best friend’s reputation with an intense blitz of publishing across all his papers. However, the media campaign is highly unpopular and large companies begin pulling their ads from The New York Banner. As the campaign continues the public backlash grows and Gail realizes that everything is on the line. His paper, reputation, wealth and most importantly: his power.

Will Gail support Roark - his confidant, spiritual equal and best friend - no matter the cost? Or will he concede to the crowd, denounce the architect and sacrifice his soul to save his media empire? Gail Wynand’s character arc is tragic. From him we learn the perils of pursuing power, and how the desire to control others leaves us vulnerable to the very people we seek to dominate.

Howard Roark

Howard Roark is perfect. He is the sinless man within the framework of Ayn Rand’s idealized universe. We often hear the trope about the artist who refuses to compromise his or her ideals. In Roark’s case it’s not that he refuses to compromise, it’s that he is physically/spiritually incapable of doing so.

At one point a penniless Roark closes his architecture office and moves to the countryside to split granite in a quarry. He does this despite having several clients who had been interested in working with him. However, the clients had asked for houses built in a style that Roark is incapable of producing. Not for a lack of talent, he is an excellent architect, but due to the spiritual inability to draw things he doesn’t love.

The penultimate example of perfection is Roark’s self-sustaining ego. Roark is described as a wholly self-powered man, a person who needs neither praise nor encouragement, nor one who can be diverted by criticism. We tend to view “ego” as a negative character trait; hubris or arrogance. Rand however views it as a positive attribute. Her vision of ego is roughly akin to positive self-image. Ego represents the characteristics and traits that distinguish one from another, and Rand is obsessed with individualism. The power of the individual over the group, personal sovereignty being the opposite of what one found in her native Soviet Russia.

Here’s Roark in his own words.

“I think the only cardinal evil on earth is that of placing your prime concern within other men. I’ve always demanded a certain quality in the people I liked. I’ve always recognized it at once—and it’s the only quality I respect in men. I chose my friends by that...A self-sufficient ego. Nothing else matters.”

As a teenager I resonated with Roark’s example because I never quite fit in. I had friends, sure, but there was always a wall between me and other people. That gap meant that I couldn’t depend on external support, I had to turn inward to find the tenacity and drive to accomplish my goals.

Today we might call this an internal versus external locus of control. Perhaps you’re familiar with these phrases? Someone with an internal locus of control believes that their actions are the primary determinate of what happens in their life. I am hardworking, intelligent and tough, therefore I shall succeed. Someone with an external locus of control believes that factors outside their control shape their life. I am a woman, my parents were not educated, I grew up in a small town with no opportunities, therefore I cannot succeed.

I deliberately mentioned being a woman, as there is evidence that women are increasingly at risk of developing an external locus of control. Here is a brief excerpt from an article on Konstantin Kisin’s Substack.

Gen Z girls are in a major mental health crisis, and as Jonathan Haidt has found, it is young liberal women who are suffering the most. In fact, 56% of liberal white women aged 18-29 have been diagnosed with a mental health condition.

One explanation for this is locus of control. Liberals tend to have a more external locus of control, meaning they feel as if their lives are governed by external forces like patriarchy or white supremacy—a perspective linked with poorer mental health outcomes. Conservatives, however, tend to think they have more control over their destinies.

As Gen Z women have become more progressive and politically active, Haidt observes that they’ve shifted psychologically. Not only have they adopted a more external locus of control (as have all of Gen Z), but embraced an ideology that encourages cognitive distortions like catastrophising and emotional reasoning. This has then caused them to become more anxious and depressed.

If you have an external locus of control you may feel powerless over your life. Not only does this make you more prone to afflictions like anxiety or depression, it makes you less effective in doing anything about it! Sustained action requires that you believe in a positive outcome, whether that’s smashing the dastardly patriarchy or becoming an architect.

Much like no Christian will ever follow Jesus’s example perfectly, none of us will ever be Howard Roark. The “perfect” man who could go a lifetime without a word of encouragement. His ego; the perpetual motion machine. Still, aiming in that direction has proven useful to me. If you’re going to operate outside the confines of normalcy you must be able to sustain your own actions with precious little outside validation.

“Men have been taught that it is a virtue to agree with others. But the creator is the man who disagrees. Men have been taught that it is a virtue to swim with the current. But the creator is the man who goes against the current. Men have been taught that it is a virtue to stand together. But the creator is the man who stands alone.”

This final sentence brings us to an interesting point: Howard Roark’s friendship with Gail Wynand. Theirs is a friendship that shouldn’t have been. Gail ruined the career of Howard’s mentor. Furthermore, Gail is driven to hoard power over other men, a practice that Roark disdains. That they end up as friends is a testament to their self-sustaining ego, intense work ethic, and their mutual backstory of rising from nothing to make a name for themselves in the crowded streets of New York.

Their friendship is worth mentioning because it leads to one of the greatest lines from the book. When Roark is asked how he can love Gail Wynand, a man who is apparently his opposite in all things, Roark replies,

Brilliant! Such a definition of love may appear sterile at first glance, but I find that there’s so much more than meets the eyes. Our friends, family members and significant others… We love them despite their character quirks that piss us off. We make an exception and excuse in them behavior we wouldn’t stand for in others, because of the totality of who they are. Gail Wynand represents everything that Howard Roark hates, yet Roark loves him as a brother.

Roark’s story is that of perseverance, staying true to one’s vision, and working hard. Roark takes many beatings because of his independent mind, but he ends the book on top of the world. Literally. It’s the perfect final scene for an especially beautiful character.

Conclusions

Written nearly a hundred years ago, The Fountainhead has held its own against the ravages of time. As we should expect from any well-crafted story, the plot, characters and lessons are just as pertinent today as they were back then. Gail Wynand wants power, Ellsworth Toohey seeks to destroy that which is good, and Howard Roark wants to build beautiful buildings and apart from that please just leave him the fuck alone. Epic!

I recognize that Atlas Shrugged has proven nearly prophetic in its predictions about modern America. In fact I wrote an entire article about it. However, it’s Atlas’s theme that I find rather impractical. When society goes to shit because the mental defects are in charge, all the productive people should give up on the world and move to a hidden commune in the mountains. Ok, I guess..?

The Fountainhead’s theme is more realistic. If you’re an artist or entrepreneur unwilling to compromise on your vision, you will face years of turmoil. You must persevere, work hard and prepare yourself for setbacks. Ultimately though, if you remain resolute you can succeed. A far more practical message, IMO.

Ellsworth Toohey has the right strategy in 2020+ (from a purely pragmatic view). People's attention spans are lower. Most people cannot watch a video longer than two minutes. A book? Most likely not.

.

It is all about dealing with the current reality and being pragmatic. It also gets into a grey area, where is the line drawn between marketing and propaganda (Edward Bernays)?

Marketing/propaganda is powerful. If something is perceived as being "popular" or "cool" or whatever else, most people (especially younger people), will go along with it.

Your essay brought back wonderful memories of reading both books a few times starting in high school. Huge influence on my life and politics. Would be great if AI could write an Ayn Rand book about Margaret Thatcher